Katie Villa’s Story

Today, I was moved to do something which I had not done since 2008. I logged on to www.pni.org.uk. I searched back through the threads. And I found my posts. From back then. From the dark days. Those first steps towards getting better. It’s strange to read them now.

They are me, I can hear my voice speaking/typing/thinking those words, and yet there is something unrecognizable too. I can hear panic in the flow of sentences, the desperate need to be heard, the jaunty exclamation marks and turns of phrase which bely the agony just beneath the surface. There was so much I didn’t say. And now I have been moved to do this. Write my story. Not from a place of finality- I do not believe my story to be over. But I do think that I can write from a place of honesty, contentment and balance.

This might ramble a little. I’m sorry if it does. Even this precursor is really just a way of putting off the inevitable. It feels like diving in to something bottomless. I don’t know how far this will take me. So here’s the beginning, I think.

I got pregnant by accident, and I discovered this during the break-up of the relationship. I am wilful, headstrong, stubborn and utterly vulnerable. I always have been. I have also spent my life pushing my body and my boundaries, conquering my fears, never sitting still. This was not the plan. I had never even held a baby, to the best of my memory. None of my friends had babies. My partner and I dropped everything and stayed together, and I decided, with little or no thought, that I was having this baby. Not only that, but I was going to have it brilliantly. I hadn’t wanted a baby. But when the dust settled from our finding out, I set about proving to the world that I DID want it.

My partner and I ‘stayed together’, in a certain sense of the word. But we were not a team.

There was no love left, but we slept in the same bed and faced the future together. I heaved a pile of pregnancy and birth books home from the library, read them page to page, made notes, memorised bits. But in retrospect, none of them were for me. My husband and I had not waited for this moment, we were not painting nurseries, I was not wearing his white shirts while I put my feet up and dreamed of the happiness to come. I was saying good bye to my life and my body. I was terribly terribly alone.

And I was very unwell. I felt sick all day every day. I could barely eat. This just wouldn’t do, as I had an agenda. I was busy proving that I was OK, that I wanted this baby, so I banished every doubting thought, lest the foetus would hear them, and I worked triple shifts and cycled up hills and went to every party that my young, carefree, healthy group of friends were throwing. I didn’t drink or smoke, but I was there. Partying with the rest of them, shouting “I’M STILL ME” while every bit of me wondered if that was still true.

Then, during the third trimester, while I ballooned but finally the sickness had lifted, I developed food allergies. But I didn’t know I had them, and so every few days I would go down with unexplained and draining sickness and diarrhoea. My frame continued to shrink. I was losing weight, while pregnant. I had always been quite buxom, and sturdy. Now I felt weak, and incapable. And I was starting to lose control. I couldn’t! I wouldn’t! So I decided on a home birth, and went to active birth yoga classes. What better way to prove how brilliant I was at having babies than to have it at home? As nature intended? I would not need drugs, oh no. I was going to have her naturally, simply, like a cave woman. So I fought on, burying my terrors and building my armour. And people fell for it, told me how amazing and brave I was, told me what a wonderful mother I would be.

The birth came around, late, but then I had had no idea of dates really. It came on one morning around 4am. I woke up calm. Quite sure. This is how it feels and I can cope with this. I put on ‘Oh Brother Where Art Thou?’, made a cup of tea and rode out each contraction. But by mid morning they were strong. They took over. There were no distractions to be had and they were coming thick and fast.

At some point, day changed to night and I found myself on all fours, exhausted, terrified, and in agony. I had expected pain. I could cope with pain. But this was beating me. I was failing. From my position, naked on the floor, begging for hospitalization, I remember thinking, very calmly, about suicide. This cold hard thought. That would stop the pain, solve all this. It wasn’t emotional at all, I was just genuinely considering it as an option. Then I realised I couldn’t even do that as there were too many people between me and the knives. And so I fell apart. My waters weren’t breaking. My parents were sent away from the front door. It was dark, I was exhausted and I was talked into gas and air. I didn’t want to. I have a phobia of feeling and being sick. It’s my Achilles heel. It’s losing control. But it happened, and so in between gasps and sobs and begging, I inhaled Entonox. I have never begged before. And I think it’s the smallest a human being can be. Now I became paranoid too, and I felt like the only drunk at the party. And then the whispering began.

You see, I had two midwives with me throughout Alice’s birth. One was my active birth yoga teacher, by chance. She was motivational, inspiring, she believed in active, engaged, strong birthing, and she knew I had wanted to stay at home. The other midwife held very different views. She had kept telling me to lie down, over the phone. I know the team was stretched that night. I had heard conversations, and people were being brought in out of hours. I was at my most vulnerable, naked and sobbing, while two people were having a bad day at work. They disagreed. They bickered in the shadows behind me whilst I writhed. In the end, the second midwife sat glowering in the corner. She played bad cop. She hadn’t introduced herself and made comments that were meant to toughen me up, but instead they broke me.

When Alice finally came, all nine pounds and seven ounces of her, I was done in. Empty. I was utterly numb. I stood in the middle of my living room, awash with blood and god knows what else, and Alice was between my feet. And we just stared at each other. And I felt nothing. I couldn’t sit or stand because I was completely ruined. And I just stood. There was no amazing moment where I looked at her, held her, felt that unconditional love. I just swayed like a ghost.

I had torn, but I was told that the second midwife would be able to do the stitches there, in the bedroom. I heard her say “I like doing stitches”. Zombie-like, I followed her in, lay down, and by the light of an angle-poise and with the rush of gas and air into my system, she stitched me up. Some time during this process, something changed. We were in there for hours. I went through two tanks of gas. She began to perspire. I had to keep asking for breaks from the gas and air as I was feeling so queasy. I kept asking her how much longer and she wouldn’t answer. My partner, who was holding the lamp, had to leave the room as he was going to pass out. My mum took his place. Later on he told me that it had looked like road kill down there. I watched the midwife losing control, and had no voice, no power of mind even, to take control. I was letting her sew me back up. This woman who did not know or care for me, was deciding how a part of my body would look, would feel, would function for the rest of my days. The most beautiful part of me no longer belonged to me.

When it was over, Alice was pressed onto my breast. She wouldn’t feed, I was too tired to ask for help, and the midwife left without a word. Two long, largely sleepless, days later, I awoke in what I assumed must be my bed, with what I assumed must be my baby. I couldn’t remember either. An out of hours doctor was called. With a worried face, he called for an ambulance. I had developed an infection, which had been left to run rampage in my body and I was tachycardic and very unwell. When we entered the room at the hospital, I angrily said that they hadn’t changed the sheets, this room smells awful. My mum quietly and lovingly told me that the smell was me. My wound. I had not been told to look out for an infection, and my body was so alien, so utterly utterly ruined by the birth that I had no idea that I had been unwell. I must have thought that was how it felt.

A couple of weeks later, back at home, when I still had no control over my bowels, I was seen by a specialist. That first degree tear that I had been told I had, that had been sewn up at home in my own bedroom, turned out to be a third degree tear. I had torn from front to back. From front to back. Standard procedure for third degree tears was apparently a general anaesthetic in an operating theatre. Mine was a back street botch job in comparison. Everybody makes mistakes and I would never blame anyone for what happened. All I wish is that when she saw her mistake, and I believe she did, that she could have admitted it. Instead, I watched her carry on regardless.

In the hospital, that first time, I had found myself in the weakest state I had ever been. I have always been active, I was a runner, I did martial arts. My body was mine and together we did impressive things. But there, I found myself hobbling to the bathroom, holding on to the furniture, and I laughed at myself. I remember thinking, come on, you’re putting this on now, just walk normally. And I couldn’t. I clung to my mother as I went to the toilet, naked, crying out in pain. And then I staggered back to bed. I was still a ghost. And a wedge had been driven between me and my body. I put my hand down there, and felt alien lumps of flesh.

Yet all along, I was told, congratulations, you had a wonderful birth, you’re doing well, let’s get you up and about. I was never allowed, I never allowed myself, to come to terms with what had happened to me. Imagine that injury through any other means. And then imagine the rest and recuperation, the sympathy and care, the time off work, the insistence that you keep your feet up. Instead I was a mother. A weak, vulnerable, terrified mother, and I was not allowed to wallow. I had a child. And I should have bonded with her by now.

Alice was a huge, demanding baby. And my body couldn’t keep up. I breast fed every two hours and watched my body shrinking away. Hers too for a while. And already I was feeling guilty, for the bond, this bond that our society shoves down our throats from all angles. I hadn’t bonded. I was broken and I wasn’t coping and this baby was killing me, and I had to hide this every thought from the baby, from the world and from myself. I felt guilty and terrified. When I think back to this time, this whole period, the first year, has a different taste and smell, that I can’t quite put my finger on. It feels slightly metallic on the tongue, pewter grey, dull and unforgiving. I was drowning in post natal illness, coupled no doubt with post-traumatic stress, and it went unnoticed.

I didn’t cry. Well I did, but that wasn’t the main symptom. I think maybe if I had, it would have been noticed. Instead, I lived in a state of constant, strangling terror. I barely slept, I was terrified of being left alone with Alice, I dreaded my partner going to work. I was constantly nervous, there was adrenalin whirring in my stomach, and I was paranoid. Later, when I was finally seeing a homeopath, I described the feeling that there was a huge, dark malevolent presence in the world, following me, hurling challenges at me that I was destined to fail, and waiting for me to die. I felt like something was trying to kill me. Day to day life was exhausting. I was desperate to be around people, but even this felt like a huge effort, and my efforts to pretend to be fine, to keep the grimace of a smile painted on my face, left the front of my neck in a constant tension. It would ache all day. Even now, six years into my recovery, when I have a bad day, this is the physical symptom that returns. That ache, that tension as my muscles tighten into the brave, rictal face that I pasted over my headlong plunge into Post natal Illness.

A homeopath who specialises in gentle talking therapy saved me. I had already been to therapy provided by the NHS which hadn’t worked. Because I had been diagnosed so late (six months in, not that late in my opinion) there wasn’t much on offer. If I had come in straight away there would have been lots, I was told. As it was I was referred to a therapist who began the first session by handing me a tissue and saying we only had two, three hour sessions together. I knew this wouldn’t even be long enough the scratch the surface and something inside me broke. My birth notes had been written by my active birth yoga midwife, who has a wonderfully sunny outlook. She had known how important a home birth was for me (she had not known the reasons why) and so my notes told the world, and my therapist, that I had had a great birth. Successful. And of course, the tear was described as minimal. So, my therapist concluded, there really was nothing to be unhappy about. But these were not my words. This was not my story.

I left that room terrified. Therapy had been the lifeline, and I had just been cast back out to sea. I contemplated suicide frequently, coldly. I rationalised that my daughter, my pure innocent daughter who I was dirtying with all my negativity and failings, would be far better off without me. I had failed then, was failing now, and would continue to fail. I was not designed to give birth. I was haunted by the thought, and I sometimes still am, that without modern medicine, I would not have survived the birth. I felt like I shouldn’t still be there. I spent nearly every waking moment following terrible things happening to my precious girl. I lived in a constant state of fear. Whenever I lay down to try and sleep, a horrific series of events would begin to play in my brain and I couldn’t stop them.

Luckily, I found something that worked for me. I saw my homeopath monthly for a while. And I would never notice the changes happening at the time. But after a while I found that, when asked, I could honestly say that I felt better. Looking back at those early, tentative improvements, I see each one as a gradual lift in resolution. Like altering the brightness setting on a screen incrementally. Things dipped for a while when I needed to go in to hospital to have my stitches properly done, under general anaesthetic. I was on a bowel ward of frail old women, and so I cried myself to sleep to the stench of faeces every night for a week. I had been terrified that I would end up back in that terribly weak state. I had been disgusted by my own frailty after the birth, but this time, I felt strengthened by the fact that I knew what I might feel. The first time had been a shock. This time, I was gently prepared.

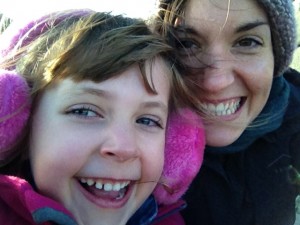

Since then, I have come to something I might call contentment. I sometimes get that taste in my mouth, but I know it. I recognise it and it doesn’t scare me as much anymore. I am now married to a new partner. And my family feels whole. My daughter is the most astoundingly beautiful creature and there are frequent moments of blissful happiness that I often experience at the most unexpected times. I sometimes think of her as my best friend. And sometimes she drives me bonkers. And sometimes she keeps me up all night with bad dreams and I worry that I won’t cope. But I do. I survive.

I have come to be content with ‘enough’. I am ‘enough’. I do not have to always be the best. I came into motherhood sobbing and begging, and always felt that I was coming up beneath this horrible, soft focus ideal of how ‘things should be’. My advice, if I am in any way wise enough to give any, which I doubt, but if you will allow me this small concession to give advice, it would be this. Don’t be sold that. Don’t let people who make money out of unhappiness and vulnerability sell you any version of happiness but your own.

There is a whole lifetime to bond with your child. Every relationship is different. My disengagement at the beginning of ours has lent a quality of wonderment and presence to our relationship. It was hard won, and none the worse for it. It’s just different and it’s never too late.

If you feel like you have been run over by a bus by pregnancy, birth and Post Natal Illness, allow it. Feel it. You are wonderful. You are. You are enough. And so am I.